An Interview With Dr. Laffer: A Weak Yen and Trade Protectionism Won’t Recover Japan’s Economy (Part 3)

The Liberty spoke with Dr. Arthur B. Laffer, the father of supply-side economics, on what it takes to restore confidence in the Japanese yen.

(Interviewer: Hanako Cho)

Cho: Some have pointed to the interest rate differential as the cause of the yen’s depreciation. What are your views on this?

Dr. Laffer: No. The interest rate differential is the consequence of the inflation and the monetary policy, not the cause of it.

There are two things on interest rates that you have to understand. This is done by economist Robert Mundell in a very short paper, but it’s very important. Let’s take a one-year bond yield of 6%. That tells me that the market expects the nominal yield on assets over the next one-year period will be equal to 6%. That’s the market’s best guess as to what will happen.

Now, what is included in that 6%? One is the rate of inflation; prices can rise. Also, there can be a real return on capital. If I do an investment and that investment has a 3% real return, that will cause the interest rate to be 3%. And if prices rise by 3% as well, that would cause the interest rate to be an additional 3% for a total of 6%.

The interest rate is the expected nominal yield over the period of maturity which is one year in this case. That will be comprised of two things: the expected real return on capital and the expected increase in the price level.

Under Reagan, How Did America Come Back from High Inflation?

Dr. Laffer: Now, let me give a good example of what happened on this, and this I was very involved with.

Inflation was very high when Reagan took office. The prime interest rate on January 29, 1981, was 21.5%. (Editor’s note: The prime interest rate is the lending rate that banks charge to their best customers with high credit ratings.)

Paul Volcker took over as the head of the Fed and he was going to get rid of that inflation with sound money. At the same time, Proposition 13 passed in California and tax cuts we retaking over everywhere. In 1978, we also passed something called the Steiger-Hansen capital gains tax cut. I worked on all of these. (Editor’s note: Steiger-Hansen capital gains tax cut was a tax break that would lower the capital gains tax from 50% at the time to 28%.)

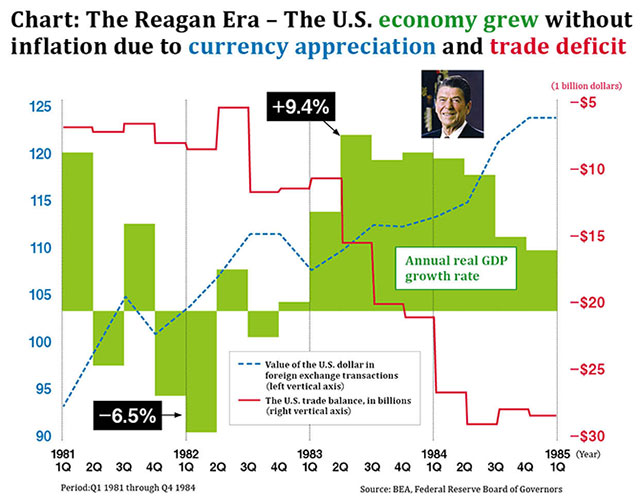

All of a sudden, there was a different America. America was coming back. We had more investment, more output. We attracted capital from the rest of the world. Interest rates and inflation came down. The real yield on capital went up. The U.S. trade balance went from balanced trade to a huge trade deficit, which is a huge capital surplus (see chart below). We went from a socialist nation to a pro-growth supply-side nation.

Why Did Tax Cuts Throw Thatcher Out of Office?

Dr. Laffer: Now, let’s compare that with what happened under [former Prime Minister of the U.K.] Margaret Thatcher.

The U.K. pegged the British pound to the German mark.

Then, she did the big tax cuts for personal income tax from 60% to 40%. That caused a huge influx of capital into Britain and caused a trade deficit and a capital surplus. Well, there was no way the exchange rate could appreciate like it did in the U.S. since the British pound was pegged to the German mark. From 1988 onwards as a result, Britain’s domestic inflation increased from 4% and below to over 10% in the late 90s which threw Lady Thatcher out of office.

The same thing happened in Ireland.

That’s where I wrote my paper, “The Luck of the Irish: Why Ireland Should Punt the Euro”. I was over there a lot when we cut the corporate tax rate way down to 12.5% and we cut personal income taxes. Ireland took off like a rabbit. Of course, they were pegged to the euro, which meant that they started running high inflation to get the terms of trade exchange and threw the government out. The same thing that threw Margaret Thatcher out of office because they kept the fixed exchange rate is exactly what happened [in Ireland].

The U.S. did not do that. We allowed the exchange rate to jump in value from 1978 to 1985. The dollar appreciated and the prices of imported goods became cheaper. Thus, the exchange rate absorbed inflationary pressures and we did not have inflation. We had a huge trade deficit, a huge capital surplus, and did we grow like any country ever on earth? That’s why I argue very strongly for tax cuts, deregulation, spending restraint, sound money, and free trade.

From January 1, 1983, to June 30, 1984, U.S. real GDP by 12%. We grew by 8% per annum by putting in supply-side economics and no inflation. In fact, inflation came down. Interest rates came down. That is possible for Japan today.

What’s the Correct Policy to Stabilize Currency?

Cho: Do you think Japan should raise interest rates?

Dr. Laffer: I think Japan should stabilize the value of currency.

Now, where does confidence in the currency come from? It’s similar to asking, what does confidence in Hanako Cho and The Liberty come from? Consistent principled responses in doing the right thing on economics.

If you have a good price rule, if you have a good tax system, you have confidence in the system. It doesn’t mean things can’t go wrong. They can. A good bank can still have some inflation. It can still have some deflation. It can still have a recession. It can have a boom. But they will do the right thing so that they can have confidence that the cause of that recession, boom, inflation or deflation will not be bad monetary policy.

If you have a good government with a flat tax, a low-rate, broad-based flat tax, spending restraints, sound money, minimal regulations and free trade, you can have confidence that the country’s policies will be those policies that will assure the chance of the best-performing economy imaginable. That is how you get confidence. Confidence in the currency comes from the Bank of Japan running monetary policy correctly like it used to do. Running good policies will give the world confidence in your country. It will give the citizens good confidence in their government.

We have had a couple of very interesting experiences when Paul Volcker came in, when Alan Greenspan came in. We didn’t have confidence in the dollar when they came in. But after they were in for a while, the dollar appreciated enormously in the foreign exchange. We had good tax cuts, free trade, minimal regulations, and confidence in the world came. Our stock market rose enormously. Our currency rose in the front. We became the world power. Meanwhile, Japan put on a big consumption tax in 1989 and the world lost confidence in Japan.

It’s pretty simple. What does confidence mean? It means competence.

Why do people work? So they can get paid after tax. Why does they want to get paid after tax? So they can buy things they want to buy for their kids, for their family, for their father. Why do countries export? So they can earn the wherewithal to import. Stop putting on tariffs. Stop the taxes. Stop the spending out of control. And that will give you confidence [in your currency].

Compare Flow vs Flow, Stock vs Stock

Cho: The Japanese government’s debt-to-GDP of 260% is way above that of the U.S. and in such case, it may be difficult to raise interest rates since that will make it harder to pay off interest. What are your thoughts on this?

Dr. Laffer: Let’s first talk about how you measure the problem. Debt-to-GDP is not the appropriate measure. You never compare a balance sheet item with an income statement item. An income statement looks at flows – income and expense – and a balance sheet looks at asset values or stocks. It looks at debt and equity. What you do want to compare if you want to analyze your debt, is to look at debt compared to wealth.

When you buy a house, they ask you, “What’s your equity?” They’re asking for your stock. When they ask you, “Can you afford the interest payments?” They compare your income to your interest cost. So that’s flow to a flow.

You should look at stock to stock, or flow to flow. When you look at that, it gives you a very different picture. I’m going to just use the U.S. picture.

U.S. debt to GDP is 99.7%. I’m looking at net debt by the way, not gross debt. There’s a lot of debt that the government owes itself, different departments and agents like the Fed. Gross debt isn’t counting intragovernmental debt. U.S. gross debt is comparable to the total mortgage amount a person has taken out from the bank. If the person has deposits held at the bank, those deposits should be netted out of any mortgage amount to look at net debt. Among economists the appropriateness of using U.S. net det is not a matter of dispute.

U.S. net debt to GDP is 99.7%. U.S. debt is about 35 trillion dollars, and you’re putting 660 billion dollars to debt service. It’s a big number but it’s between 2% to 3% of GDP so that’s not the end of the world. If 3% of your income went to debt service, you’re not in trouble. Context matters, just as how rich people with higher incomes can handle more debt than poor people with low incomes.

U.S. wealth is about 180 trillion dollars. When you look at U.S. debt as 35 trillion, 35 to 180 is a lot of debt, but it’s not “Ah!” When you use a bad measure, it tends to push you to either not think of it seriously or because you get scared by it. You’ve got to be very, very careful how you look at debt-to-GDP, both of which give you a very different answer and a much less scary answer.

The Problem Isn’t Debt. It’s the Spread.

Cho: What are your thoughts on national debt?

Dr. Laffer: Let me ask you the question this way. I’m going to let you borrow all you want at 1% interest. And I’m going to let you invest all you want at 10% interest, risk-free. How much would you like to borrow? As much as you can get your hands on, alright? Now, reverse those numbers. I’m going to let you borrow all you want at 10% interest and let you invest all you want at 1% interest. How much do you want to borrow? None.

It’s not the debt that’s the problem. It’s the spread. Now, if I can borrow a lot and go into debt by creating huge wealth increases, it’s wonderful. But if I borrow to lose money, I’m in trouble.

How Did Reagan Administration Win the Cold War?

Dr. Laffer: In reality, the Reagan administration was able to make appropriate investments and save America (refer to the column).

We had just followed the Four Stooges – Johnson, Nixon, Ford and Carter – the worst four presidents ever on earth, when we came onto the scene, when God still loved America, they had run America into the ground. Everything was collapsed.

But we dug in the rubble and we found this little plaque, this little sign, that said, Enterprise America. We polished it in our jacket and now it was shiny Enterprise America. We stuck it on the front door of the White House, and we borrowed lots and lots of money. We invested in defense to have security in the U.S. We deregulated the economy. We cut tax rates and rewarded hard work and effort. The stock market soared.

We borrowed, we had huge deficits, we increased the national debt dramatically, and we created Enterprise America. The wealth of America went way, way up because of tax rates and pro-growth policy.

We did it by borrowing, but we borrowed for the right reasons. We borrowed at low interest rates and invested at a high return. Now take Jimmy Carter, Barack Obama, George W. Bush, George H. W. Bush who borrowed lots and lots of money to pay people not to work. These guys paid them to give transfer payments.

This is happening in Japan, the U.S., and it’s the worst of all possible worlds. It’s how you borrow, what the returns are and the cost of borrowing to the return to the money. The best of all possible worlds is when you borrow from the cheapest source and invest in the highest return source. It’s not the debt that’s a killer. It’s the spread.

Let Old People Work, and the Social Security Problem Will Solve Itself

Dr. Laffer: My father retired at 65, lived another 11 years, died at 76. That was right. He should have retired at 65. He was old, he was tired. He had problems with health and all that. Everyone back then did. But they don’t now. I go back to my class reunion at Yale or my prep school reunion, and there are a lot of old people sitting around there still working. You’ve got to reflect the world. Old people in Japan can still work. And there’s no reason why young people should pay them not to work. The school guards, the people are the stores who greet you at the door, aren’t they old? I know what Japan is like. The offices are clean. The people work hard. They’re very polite. When I look at Japan, I really think those people want to work. They want to be contributors to society, not just waiting to die.

If it were up to me, I would cut government spending and especially the payments to the elderly. I’d raise the age of retirement from 61 to 80. And they’d much rather work. Let old people work, and you have no social security problem. You have no aging problem whatsoever. You’re picking on old people and the government is pitting the old people against the young people, but there is no natural enemy. Old people and young people are friends, not enemies. You are killing the old people by paying them not to work. And you’re killing your country and the young people.

Cho: I think by 2050, the population over age 65 will account for 40% of our population.

Dr. Laffer: Do you want to know the really scary number? The United Nations do a population forecast, and they announced that a century from now, with the continuing trend, there will be 24 million Japanese people. There will be a huge reduction in Japan. Japan is dying. This is a joke, but the Japanese girls and guys are pretty and handsome. There’s no reason they don’t have babies. It’s because of the policies of the government. The world’s going to lose a very important and wonderful country because of this.

If Redistribution Continues, No One Will Earn Income

Cho: The rapid increase in Japan’s government debt seems to be one of the reasons why confidence in the yen is declining.

Dr. Laffer: Yes. Do you remember my transfer theorem? As I explained, a transfer takes from one group and gives to another group. It takes from the young workers and gives to the old people. That’s a transfer. They can do it from young to old, from small to large, from boy to girl, whatever. These transfers can occur. The way we usually think of it is from rich to poor. You take from the rich, and you give to the poor.

Let me give you this transfer theorem, verbally, a proof. A transfer theorem is when you take from someone who has a little bit more and you give to someone who has a little bit less. Now, by taking from someone who has a little bit more, you reduce that person’s incentives to work and that person will work a little bit less.

Now, by giving to that person who has a little bit less, you provide that person with an alternative source of income other than working, and that person, too, will produce a little bit less.

It’s a theorem here, and it’s math. It’s not left wing or right wing. It’s not good guy or bad guy. It’s not Republican or Democrat. It’s not liberal or conservative. It has nothing to do with what your political leanings are, your age, your gender, what country you come from or anything else. Whenever you redistribute income, you always reduce total income.

What is Japan doing? It’s redistributing income. If you tax people who work and you pay people who don’t work, you’re going to get less people working.

Now, let me do the lemma from that theorem with you. I’m not going to prove it verbally with you, but you can see it intuitively. The more you redistribute, the greater will be the reduction in total income.

Now, the limit function of this theorem is really important here. If you were able to redistribute the income so that everyone came out exactly the same, if you could have perfect redistribution so everyone comes out the exact same, the limit function of this theorem is there will be no income whatsoever.

Bernie Sanders, Elizabeth Warren, Japanese socialist Hirofumi Uzawa, they don’t understand this.

In order to get everyone to come out exactly the same, you’d have to tax everyone who earns above the average income 100% of the excess and subsidize everyone below the average income, 100% up to the average income. You have to take from those who make more and bring them right down to the average, and give it to those who make less to bring them up to the average.

Only that way can everyone come out exactly the same.

If you actually taxed everyone above the average income 100% of their income above the average, and if you actually subsidized everyone below the average income up to the average, we’ll all come out even at zero. There will be no income whatsoever. Japan’s government needs to see this theorem on TV every day, twice a day. They need to understand this. They need to understand this is what’s happening. This is your transfer theorem right here. It’s not complicated, but this is Japan right here. That’s what’s killing you.

Our government doesn’t understand it either by the way, but we understand it a little bit better than Japan.

Editor’s Column 1: ‘Borrowing to Win the Cold War Was a Good Investment’

It is sometimes said that the Reagan administration caused the national debt level to skyrocket. But his tax cuts were not the primary reason. Most of the deficit increase was due to the massive increase in defense spending in the 1980s.

In fact, thanks to the Reagan tax cuts, revenues increased by 24% in real terms. Revenues between 1950 and 2005 averaged 19% of GDP, higher than the postwar average of 18.4%. It’s not true that the Republican tax cuts led to a budget deficit of nearly $300 billion.

As the U.S. and the Soviet Union engaged in an arms race, the Soviet defense budget rose by several tens of percent, eventually accounting for about half of the national budget.

Meanwhile, the total increase in the U.S. defense budget from 1981 to 1989 amounted to $806 billion, but the U.S. defense budget under the Reagan administration was no more than 6% of U.S. GDP which boomed under Reagan. If there had been no economic growth at that time due to the Reagan tax cuts, there would’ve been no revenue growth to support the increasing defense spending. U.S. economic growth through supply-side economics forced the Soviet Union to adopt a cost strategy.

Dr. Laffer believes that debt in itself is “neither good nor bad” (“Tax Revenues And Deficits: Part Two”).

He is opposed to “redistribution” or transfers that brings down a country, such as President Barack Obama and President George W. Bush who borrowed money to pay people for not working. However, he considers Reagan’s “borrowing” to be a good, appropriate debt as it was necessary in order to win the Cold War against the Soviets and remove foreign threat and brought about a high return (“Tax Revenues And Deficits: Part Two”).

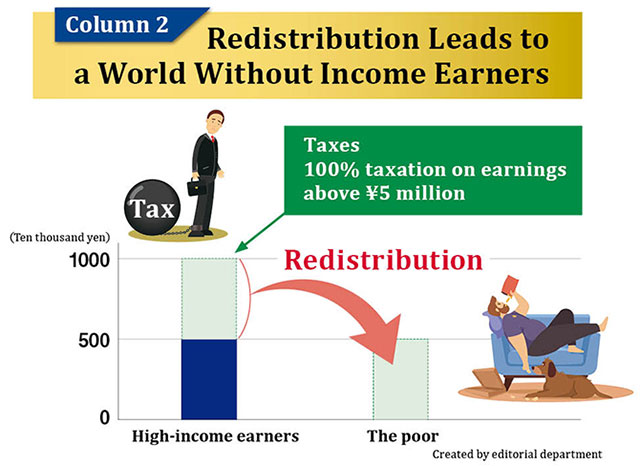

Column 2: Redistribution Leads to a World Without Income Earners

For example, if the Japanese government imposes a 100% tax on income in excess of ¥5 million for those earning ¥10 million, and distributes it to those who do not earn money, they will stop working so that from the following year onward they will only generate income worth ¥5 million, not ¥10 million. If the government repeats taxation and redistribution in such a way that in the following year it taxes 100% of income over ¥2.5 million, half of the ¥5 million, and in the year after that it taxes 100% of income over ¥1.25 million, then we’ll have a world where no one earns, or as Dr. Laffer says, “If you could have perfect redistribution so everyone comes out the exact same, there will be no income whatsoever.”