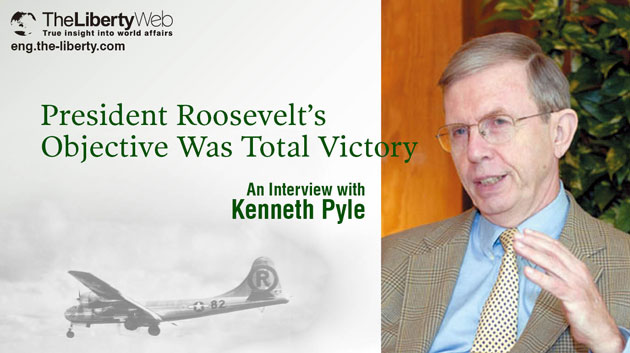

President Roosevelt’s Objective Was Total Victory

An Interview with Kenneth Pyle

Q: How do historians judge the past?

A: Writing history is still much more of an art than a science. Historians don’t come to final conclusive judgments that represent “the judgments of history.” Only the Almighty—only our Good Lord— does that.

Historians do not dispense objective truth. The perspective on the past is constantly shifting. It is sometimes said that history must be rewritten for each new generation, to accord with its concerns and its perspectives. In a real sense, it can be said that the past is determined by the present.

Kurosawa Akira’s 1950 film Rashomon was made to demonstrate this point about the relativity of historical judgment. Kurosawa leaves the implication that truth is relative to the individual and that humans are incapable of judging reality.

Historians often differ in their interpretations, such as difference in motivation, selectivity in emphasis, generational and national perspectives, bias, academic discipline, levels of analysis, and appearance of new materials of historical evidence. We can see how interpretations are relative to the circumstances of the individual writer, the time in which the historian wrote, the choice of focus given by the author, and many other factors.

Q: This year marks the 70th anniversary of WW2. What are generally people’s opinions over the decision to drop of atomic bombs over Hiroshima and Nagasaki?

A: For many years I have taught an honors seminar that studies the issues raised by the Hiroshima decision. Students have an opportunity to debate among themselves the difficult and troubling issues and the reasons why historians looking at the same succession of events have come to sharply different interpretations.

In 1999, in a poll taken of leading American journalists and historians, the decision to use the atomic bomb on Hiroshima and Nagasaki was chosen as the most important event of the 20th century.

At the popular level, public opinion polls in recent years show that the American and the Japanese people view the decision in opposite ways. Three-quarters of the Japanese believe that Japan was on the verge of surrender and the bombing was unnecessary. On the other hand, two-thirds of Americans believe that the bombing was necessary in order to avert an invasion and save massive American casualties.

Still, it is also true that many, perhaps most, Americans have had a sense of unease about having been the only nation to use the bomb. We find it difficult to square with our belief that we are a nation of exceptional virtue and we find it painful when foreign observers remind us of the decision.

In 2003 when President Bush announced the invasion of Iraq, Nelson Mandela angrily questioned American self-righteousness in light of Hiroshima and Nagasaki. Mandela said, “Who are they now to pretend that they are policemen of the world?”

The leading Israeli scholar of modern Japanese history in a recent lecture on the bombing reached the harsh judgment that “Auschwitz and Hiroshima … represented a new level of atrocity that human beings can perpetrate on each other.”

From the start, participants themselves, concerned with their place in history, sought to influence and shape the judgments of history. The most important attempt in this regard was an article written in 1947 in Harper’s Magazine by Henry Stimson entitled “The Decision to Use the Atomic Bomb.” Stimson, as Roosevelt’s Secretary of War, had been charged with the awful responsibility of overseeing the development and use of the bomb. The president of Harvard James Conant, a chemist, who served during the war as head of the National Defense Research Committee and was involved in the decision, encouraged Stimson to write a defense, worried that issues of the morality of the use of the bomb would arise in the future.

Stimson wrote to President Truman that his article was “intended to satisfy the doubts of that rather difficult class of the community which will have charge of the education of the next generation, namely educators and historians.”

Q: Which issues specifically have caused historians controversy over the atomic bombings? Would you please provide us with some background information to put those arguments into perspective?

A: Fearful that Hitler might develop the bomb first, FDR in 1941 launched the top secret Manhattan Project which in less than three years cost over $2 billion (tens of billions in today’s dollars), employed 150,000 persons.

Britain shared in the details of the Manhattan project. By late 1944 we knew that Germany would be defeated before the bomb was ready and in a secret agreement (which even Stimson did not know of), FDR and Churchill agreed at Hyde Park in the autumn of 1944 that once the atomic bomb was ready “it might perhaps, after mature consideration, be used against the Japanese, who should be warned that this bombardment will be repeated until they surrender.”

This was the only policy guideline FDR left behind when he died on April 12, 1945 and Truman knew virtually nothing of the project until nearly two weeks after he became president. Stimson and Groves came to the White House and briefed the uninformed and inexperienced new president. Stimson told Truman: “Within four months we shall in all probability have completed the most terrible weapon ever known in human history, one bomb of which could destroy a whole city.”

It was unanimously agreed that the bomb should be used against Japan as soon as possible. They ruled out the possibility of a warning or a demonstration. The Interim Committee’s deliberations about the use of the bomb seem surprisingly brief.

In July 1945 Stalin, Churchill, and Truman met at Potsdam. Truman received word of the successful testing of the bomb at Alamogordo in the desert of New Mexico and casually mentioned to Stalin that we had developed a highly destructive new weapon and Stalin feigned indifference.

Truman authorized an ultimatum to Japan known as the Potsdam Declaration which called on Japan to surrender unconditionally or face prompt and utter destruction. The Potsdam Declaration said that the allies would occupy Japan to disarm it and establish a new order in accord with the freely expressed will of the Japanese people. But there were three significant omissions. The Potsdam Declaration made no mention of the bomb or of Russia’s impending entry and it also made no mention of the fate of the emperor which was critical to the Japanese leadership.

The new Secretary of State James Byrnes argued, and Truman agreed, that the president would be “crucified” politically if he were to abandon the policy of unconditional surrender which had the overwhelming support of the American people. Two days after the Potsdam Declaration was broadcast, Prime Minister Suzuki Kantaro, perhaps regarding the broadcast as propaganda, said that Japan would ignore it, using the word mokusatsu, literally meaning “to kill by silence” which was interpreted in Washington as rejection.

The list of targets had already been determined. General Groves wanted to hit Kyoto, the magnificent and historic ancient capital of Japan. But Stimson, personally familiar with the history and beauty of the city, would not hear of it and blocked every effort of Groves to target it. On August 6, the uranium bomb, nicknamed “Little Boy”, was dropped on the center of Hiroshima.

On August 8, Russia entered the war and the Red Army swarmed into Manchuria. Rather than wait for Japanese reaction to the first bomb, General Groves had decided that hitting a second city swiftly would maximize the psychological impact. This decision was left to the military.

The city recommended as the target for the third atomic bomb was Tokyo.

Historical controversy has revolved around several issues:

- Was it necessary to use the bomb: was not Japan already defeated and on the verge of surrender?

- Were there not viable alternatives such as a demonstration of the bomb or a naval blockade or modification of unconditional surrender policy or waiting for Soviet entry into the war?

- Was the second bomb on Nagasaki necessary?

- Did use of the bomb save lives by averting an invasion?

- Were the bombs morally justified?

Historians have come to no consensus on these issues.

Q: There’s an authoritative, official, American narrative on the droppings of the atomic bombs. However, there are also alternative versions of the story. Would you please explain the historical revisionist’s approach to the record?

A:The orthodox interpretation prevailed until the arrival of a new generation of historians in the 1960s and 1970s, known as the revisionists, who made a very different kind of judgment.

It was the time when the U.S. began ground combat and bombing on a large scale in Vietnam. A generation of historians, repelled by American policy in Vietnam offered a new view of the American past as aggressive and imperialistic in nature. The fact that America had been the first nation to use the bomb and to use it on an Asian nation that was already seemingly defeated confirmed their view more decisively than any other event that American foreign policy had a history of immoral behavior.

The revisionists found many reasons to revise the orthodox view.

Why drop the bomb if Japan was on the verge of surrender? Why the three significant omissions in the Potsdam Declaration? Why no demonstration of the bomb? Why not wait for Russian entry into the war before using the bomb? Probably the most persuasive evidence that revisionists cited was the opposition to the bomb’s use that was expressed after the war by the highest ranking U.S. military figures. They pointed out that Eisenhower, MacArthur, and Truman’s own Chairman of the Joint Chiefs, Admiral Leahy opposed its use as unnecessary.

Admiral Leahy wrote in his memoirs:

The Japanese were already defeated and ready to surrender because of the effective sea blockade and the successful bombing with conventional weapons . . .My own feeling is that in being the first to use it, we had adopted an ethical standard common to the barbarians of the Dark Ages.

If some American military figures in their postwar recollections saw it as unnecessary then why was it used? In sum, revisionist historians have argued that once the bomb was perfected American leaders no longer wanted Russian entry into the war against Japan. The bomb would strengthen America’s diplomatic hand in negotiations with Stalin over Europe.

Q: America’s elite wished to fight a war to end all wars with America as the victor. Did this motivation influence Truman’s decision to ask for an unconditional surrender from Japan?

A: General Groves later said that the new and inexperienced president, who was committed to continuing the Roosevelt legacy, was swept along by the circumstances “like a boy on a toboggan.” Truman’s decision, Groves said, amounted to a decision not to interfere with the unconditional surrender policy and the existing plans to use the bomb.

The unconditional surrender policy, which Roosevelt had announced in his meeting with Churchill at Casablanca in January 1943, was a radical and unprecedented policy. Churchill and Stalin had deep doubts about the policy, but Roosevelt made his own foreign policy.

Ruling out any confidential discussion with the enemy as a basis for ending the conflict, Roosevelt cast the war in moral terms as a crusade to rid the world once and for all of militarism. Rather than fight the war to an armistice and a negotiated peace agreement as all other foreign wars in American history have been waged, this would be fought to total, absolute victory. There was no effort to privately negotiate with the Japanese or even to discuss or clarify terms for ending the war.

Roosevelt included sweeping goals in his policy:

- unconditional surrender of Japanese sovereignty and allied occupation of the entire country,

- dissolution of the Japanese empire,

- war crimes trials of the Japanese leaders,

- permanent disarmament of Japan,

- democratization of Japan’s political structure, its economic system, and its society

- re-education of the Japanese people.

FDR had many reasons for these radical goals. He wanted to rally American opinion with crusading ideological war aims that would unite a country that had only recently been isolationist. Most important, unconditional surrender policy was part and parcel of the American determination to create a new world order. Roosevelt intended to use American power to build a liberal, democratic world order, based on American values, which he believed would require total victory.

Q: What difficulties did the policy of unconditional surrender create?

A: There were, as I see it, many problems with unconditional surrender policy.

First, it provoked unconditional resistance. The Japanese military leadership determined on all out resistance. Those Japanese leaders inclined toward ending the war were left in the dark as to what unconditional surrender would entail and were handicapped in their efforts to change the military’s die-hard resistance.

Second, unconditional surrender policy became deeply embedded in American public opinion, creating a powerful momentum against any compromise. Reacting to the provocation of Pearl Harbor and Japanese wartime atrocities and reflecting a deep racial antagonism, American opinion came to overwhelming support of his policy.

American historian Allan Nevins wrote, “No foe has been so detested as were the Japanese.” American public opinion by 9 to 1 in the summer of 1945 supported unconditional surrender even if it required an invasion.

Third, unconditional surrender by its uncompromising character required the American military to take the most extreme measures to achieve this goal—either a bloody and costly invasion of the Japanese homeland or a protracted naval blockade to starve the Japanese people or continuation of the firebombing of cities —or, when it became available, the atomic bomb. In all, over 60 Japanese cities were devastated by firebombing. During the last year, civilian populations were deliberately targeted to try to break Japanese morale and a half million perished.

Fourth, if the purpose of war is to achieve concrete political objectives that could not be obtained by diplomacy, this policy abandoned the pragmatic political goals which had brought on war in the first place, namely our insistence on Japanese withdrawal from the continent. Instead of that concrete aim, the goal became total submission of the enemy and the total remaking of its government, economy and society.

The Stanford historian David Kennedy in his magisterial history of the Roosevelt era concludes that Americans might reflect “with some discomfort…on how their leaders’ stubborn insistence on unconditional surrender had led to the incineration of hundreds of thousands of already defeated Japanese, first by fire raids, then by nuclear blast; on how poorly Franklin Roosevelt had prepared for the postwar era, on how foolishly he had banked on goodwill and personal charm to compose the conflicting interests of nations….”