An Interview With Dr. Laffer: Japan Won’t Recover Amid a Weaker Yen and Trade Protectionism (Part 2)

The Grand Illusion, ‘Trade Surplus = Good’

Continuing from the previous interview, how does Dr. Arthur B. Laffer, the father of supply-side economics, view Japan’s outlook?

(Interviewer: Hanako Cho)

Dr. Laffer: I’m going to give you two examples of trade: one pro-Japan and one anti-Japan.

Imagine Japan under former Prime Minister Obuchi who cuts tax rates in Japan dramatically. What happens to the Japanese stock market? Boom. It goes way up. Now everyone wants to invest in Japan.

How do foreigners invest, net, in Japan? You as an individual can take your dollars and go buy Japanese yen, and then buy Japanese stocks or whatever else that you can. But who would sell you the yen? Unfortunately, it’s someone who wants to get out of Japan into the other country, alright? In other words, if you buy yen, someone’s got to sell you the yen. So it’s a zero-sum game.

If I buy 100 yen with dollars, someone has to buy dollars with 100 yen. Therefore, there’s no change. One American now owns yen and not dollars, and the other American now owns dollars, not yen. There’s no net movement at all, so there’s no net investment in Japan.

What Does a Japanese Trade Deficit Really Mean?

Dr. Laffer: The only way we can invest, net, in Japan is if we sell more goods to Japan and we buy less goods from Japan. If we sell more goods to Japan, what that means is we earn yen from selling those, and by buying less goods from Japan, we lose less yen to the Japanese. So we are basically buying yen with the trade balance.

Balance of payments comes from two things: the capital balance and the trade balance. Both of them are important for a country. (Editor’s note: Dr. Laffer uses the phrase “trade balance” as opposed to a “current account balance” to focus specifically on profit from trade as opposed to including foreign dividend income and other factors.)

The reason why Japan ran a capital surplus in this case is that they cut taxes and became much more attractive for foreign investors who wanted to invest in Japan.

The only way they could invest, net, in Japan is by selling more goods to Japan, buying less goods from Japan. The Japanese trade deficit is the Japanese capital surplus, which is the most wonderful thing. Japan becomes the capital magnet.

After World War II, Japan imported capital to employ Japanese, to increase productivity, to be the leader in growth in the world. This is what they did back then. They ran trade deficits, capital surpluses and look at their growth rates. This is what I mean by pro-Japan trade. (Editor’s note: Japan’s trade was on a deficit track during its period of rapid growth. Dr. Laffer’s take on this is that Japan achieved post-war economic growth because of its trade deficit, and thus, a capital surplus.)

Is a Trade Surplus Beneficial for Today’s Japan?

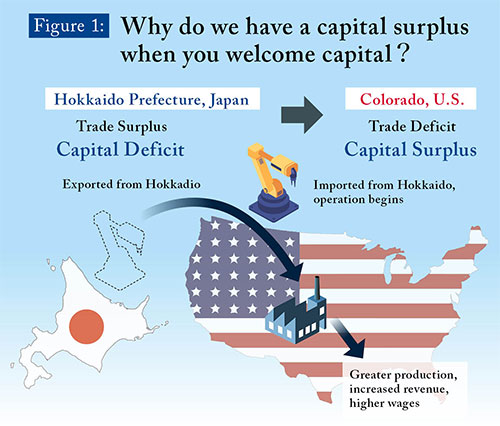

Dr. Laffer: Now, let me do the other “anti-Japan” example of trade. Let’s imagine a machine up in Hokkaido. It’s running but it’s running at a loss so we take that machine and we put it on the back of the truck and take that machine down to Tokyo Harbor. You put it on a ship and send that ship over to the United States. Let’s say you take that machine up to Colorado and put it in a factory, and now, that machine is making money in Denver, Colorado.

It’s a Japanese export; it’s a U.S. import. It’s a Japanese trade surplus; it’s a U.S. trade deficit. It’s a Japanese capital deficit because that capital machine is no longer in Japan, but it’s a U.S. capital surplus because now we have one more machine than we had.

Which would you rather be? Would you rather be importing capital into Japan and creating more output, employment and production? Or would you rather be exporting all of your capital equipment to the United States and losing production, output and employment?

Imagine it this way. Which would you rather have: capital lined up on your borders trying to get into your country or trying to get out of your country?

Of course, you’d want to be the country that attracts capital, that has a good stock market. The trade deficit is the capital surplus.

The Volume of Exports and Imports Depend on Your ‘Attractiveness to Capital’

Dr. Laffer: The reason you export more and import less, or import more and export less, is because of your attractiveness to capital. If you have tax cuts in Japan and economic growth, you’ll attract capital from everywhere and you’ll run a trade deficit and a capital surplus.

I’m going through this with you slowly, and please forgive me because it bears a lot of relevance today.

There are two principles that are very important. One is Sydney Alexander’s absorption approach (*1) and the other is David Ricardo’s comparative advantage (*2) as I explained before.

Editor’s Sidenote:

(*1): While politicians tend to think that a weaker dollar leads to more exports and thus lead to a smaller trade deficit, the absorption approach holds the idea that a trade deficit is not determined by the exchange rate, but rather, a greater demand above supply leads to higher consumption and greater imports, which creates a trade deficit. In other words, the Sydney Alexander absorption approach attributes a trade deficit to the difference between domestic supply and demand.

(*2): David Ricardo proposed the comparative advantage theory as it relates to foreign trade or international delegation of roles; this theory states that when you compare the cost of production of individual goods with another country and you export advantageous goods (meaning a relatively lower cost of production) while you import goods that cost more to produce than what it would cost another country, both parties will benefit from the trade.

Japan has had a traditional position where they’re exporting capital and running a capital deficit and where their comparative advantage is being sacrificed very much because of tariffs and quotas.

Recall Sydney Alexander’s absorption approach that the reason for running a trade deficit is created when there is more domestic demand over supply. Tariffs and quotas don’t fulfill this demand so they don’t help resolve your trade deficit, but rather, they destroy the gains from trade.

As I said before, people export in order to import. The only reason you want to export to a country is to buy goods from a country.

When you buy capital goods from another country, that’s called a trade deficit and a capital surplus. That’s what great countries do when they have good policies (refer to the editor’s column below).

You’re running a trade surplus because you’re declining. Not that the U.S. is the greatest in the world, but we’re better than Japan’s policies by the way. Sorry. (Editor’s Note: When a country produces goods, the goods are consumed domestically in a normal scenario; however, when there is no domestic demand there is no consumption, and those goods must be exported. Dr. Laffer is referring to a “decline” in which there is a smaller market due to lower domestic demand.)

The Biggest Beneficiary of Free Trade Is Japan

Dr. Laffer: Japan is a small island. You don’t have all the oil in the world. Because you’re small, you have to specialize. The gains from trade for smaller countries or isolated countries are much more important than they are for other countries.

Think of the U.S. and Puerto Rico. Who benefits most from trade? If there are just two countries in the world, the U.S. and Puerto Rico, the absolute gains from trade are the same, but the gains from trade per person are almost exclusively to Puerto Rico and very little to the U.S.

Japan as a country is desperately involved with the gains from trade. It’s about the location, its industry concentration, its capital-labor ratios. All of that means that Japan really depends on trade for the gains from trade. Their protectionism hurts them the most. The biggest beneficiary of free trade in Japan will be Japan. The U.S. will also benefit from free trade. It will, very much so.

The freer the trade is, the greater will be the gains from trade. The more tariffs, the more quotas, the lower the gains from trade.

How Would Dr. Laffer Lead Japan?

Cho: What would you do if you were the emperor of Japan?

Dr. Laffer: I love the Japanese people more than anything What would I do with my love for Japan and the people? There are two things I’d do. First, I would get rid of all trade barriers, tariffs, quotas, and I’d get rid of all non-tariff barriers with a few exceptions like nuclear weapons. Then, for the trade balance and for capital formation, I’d cut tax rates and government spending and regulation in the economy to create a political economy of growth in Japan. That would be the best thing I could do for the Japanese people, for everyone in Japan would benefit enormously from that because of the gains from trade.

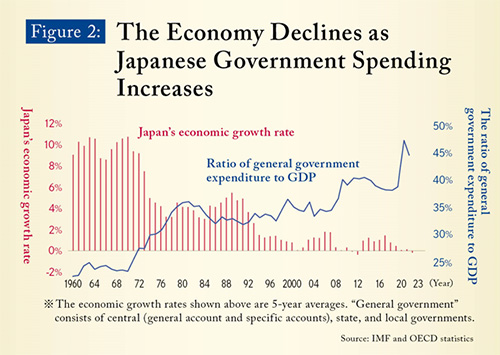

I’d then take this government spending as a share of GDP and cut it way down. I’d stop taxing people who work and pay people who don’t work. I’d stop that.

Therefore, I’d make it much more attractive for people to invest in Japan. And so I would cut government spending, deregulate the economy and let free enterprise come into Japan just the way it was immediately following World War II.

You can see the growth rate of Japan here in this graph.

I mean, do you realize how fast Japan grew? No other country has ever done that, Hanako, no country. Not even the Chinese.

I would bring Japan back to being that. As a world, we need a strong, healthy, robust, prosperous Japan. That’s what I would do if I were the emperor and I loved, loved, loved all of the Japanese people. That would be the best thing I could do for the Japanese people.

The Mistake Behind Japan’s Monetary Policy

Dr. Laffer: Japan used to be the global currency. The Bank of Japan loused up tax policy in 1989 and implemented the consumption tax but still, the Bank of Japan kept the yen solid, strong.

Guess what they’re doing now? They’re finally getting rid of the one good policy they had.

Buying all of those bonds and inflating the Japanese central bank’s budget balance sheet, printing money, devaluating the yen. That is exactly what’s happening. And you can see the inflation rates narrowing dramatically.

When you have inflation, the value of your currency goes down but politicians think if you devalue your currency, it makes you export more and import less. That’s not true. What happens if you devalue your currency is it means your prices rise relative to their prices. That’s it.

If you want to have a good exchange, do not confuse the gains from trade with an exchange rate, which is what your Japanese politicians confuse.

To counter inflation, the more stable the currency, or the stronger the currency, the better. Larry Kudlow calls it, “King Dollar.” You don’t want a weak currency.

Japan had a strong currency for the longest time, which made Japan the envy of the world. The Japanese yen was such an alternative currency for the world because they did a good job. Now they’re not.

Why Is a Stable Currency Important?

Dr. Laffer: How would I run the Bank of Japan? You want stable prices. That’s all you want.

I want to be able to trade with you. I want to lend you 200 million yen, and I want to know that those yen 10 years from now are worth exactly what they’re worth today so there’s no inflation reducing the 200 million yen. If you and I both know what the value of the yen is going to be 10, 15, 20 years from now, we can make a contract. I can lend you and know what the interest is.

To get good capital markets, you need a very stable price level. Capital formation and capital markets require stable currency, and that is the only thing the Japanese Bank should do. They should run it for stable prices.

Now, once they have stable prices and a stable currency, they would find themselves being the darling of the international countries. Everyone would like to tie their currency to the yen.

Three years ago, I’d done a proposal for former Prime Minister Imran Khan in Pakistan. One of my suggestions was to peg the Pakistan rupee to the euro. Maybe they could peg it to the British pound, the Chinese yuan, the U.S. dollar. If history were our guide, I would much prefer to peg it to the Japanese yen. That’s not true anymore.

The whole key to Japan should be stable prices for good capital markets. You need stable prices to become a global currency and collect the seigniorage gains from everyone having their currency in Japan.

The Japanese Yen Will Become a Death Spiral

Cho: How low will the yen go? Where does it stop?

Dr. Laffer: It doesn’t. Once the yen starts depreciating, inflation gets higher. With inflation getting higher and interest rates getting higher, people will want to hold less yen. Holding less yen will cause the inflation to increase, which will cause them to then have to support them. It becomes a death spiral.

You can see that before the euro in currencies like the Italian lira. You can see it right now in the British pound. You can see that formerly in South American currencies. You can see it in Zimbabwe. You get those currencies in Africa that have eight followed by 400 zeros.

It’s the same process that happens in Japan. It’s just in slow motion. It’s bad for Japan. There is no limit to how far down the yen can go. There is no limit. The process feeds on itself. As you can see, it becomes a death spiral.