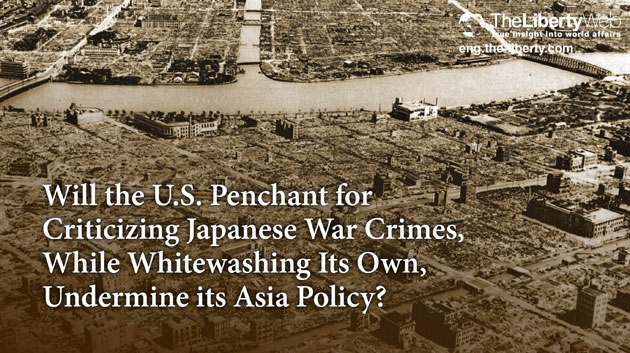

Will the U.S. Penchant for Criticizing Japanese War Crimes, While Whitewashing Its Own, Undermine its Asia Policy?

On December 10th, renowned columnist Richard Cohen published an article in the Washington Post. The article was a litany of indictments targeting Japan’s alleged war crimes from 70 years ago. So slanted and one-sided was his narrative, that one might have mistaken the author for being a comfort woman or a POW himself.

On December 10th, renowned columnist Richard Cohen published an article in the Washington Post. The article was a litany of indictments targeting Japan’s alleged war crimes from 70 years ago. So slanted and one-sided was his narrative, that one might have mistaken the author for being a comfort woman or a POW himself.

Mr. Cohen claimed that “with an implied nod from Abe, they have put enormous pressure on the Asahi Shimbun newspaper to retract stories exposing Japan’s conscription of thousands of women to serve as sex slaves for the military during the war. Increasingly, this historic fact is being denounced as a fiction. Too many witnesses – not to mention victims – insist otherwise.”

Let’s deconstruct his statement.

First, Asahi Shimbun was being denounced for reporting as fact the confessions of Seiji Yoshida (which were later discredited, and to which he admitted as being a fabrication), that he forced Korean women into sexual slavery during the war. People have been criticizing the Asahi Shimbun for its lack of journalistic due diligence for not looking into the veracity of Seiji’s story. It’s also noteworthy that Asahi’s reports on Seiji lit the flames of this controversy, and heavily influenced the Kono Statement, where the Japanese government admitted to its wartime history of forced prostitution. To think that the government’s admission was based on a fabrication should be enough to make most honest journalists return to investigating primary source materials when discussing this issue.

Second, speaking of journalistic due diligence, it is appalling that Mr. Cohen would condemn an entire nation and its people by claiming that “Japan has much to atone for”, without presenting any primary source evidence whatsoever regarding how Japan allegedly forced women into prostitution. Such a broad condemnation requires a little more investigative rigor than his cavalier attitude that was equivalent to saying “well, the women said they were victims, so it must be true”.

I would kindly point Mr. Cohen to the “Nazi War Crimes & Japanese Imperial Government Records”, which the Interagency Working Group (IWG) published in 2007. After spending $30 million and sorting through 8.5 million newly declassified documents from WW2 (yes, primary source), the IWG was unable to find anything remotely close to primary source documents that gave credence to the story of forced prostitution. Shockingly, the IWG authors even issued an apology in the report to anti-Japanese groups who had been looking for any evidence of Japanese war crimes.

Mr. Cohen went on to discuss Unit 731, the soon-to-be-released film “Unbroken”, and the Japanese treatment of Allied POWs in general.

However, “Unbroken” is based on a novel filled with inaccuracies and outright falsehoods.

The novel contains accusations that the Japanese soldiers engaged in ritual acts of cannibalism, but those with even the most superficial understanding of Japanese culture know that there are no such “rituals” or customs in its history. While individual cases of cannibalism may have existed, as they did across many fronts of the war, to suggest that this was ingrained in the Japanese culture or that it was systemic stretches the facts beyond credibility.

In the U.S., historians have described the so-called Bataan Death March as if the prisoners were walked in circles until they died for the amusement of their captors, but this incident also highlights the gulf between impression and fact. By the time the 76,000 Allied forces surrendered at Bataan, their supplies had more or less been exhausted. With Japanese forces not having extra food to spare, the choice for those POWs was to stay and starve, or to be transported to a detention facility. Initial Japanese estimates for the number of POWs they expected to capture was 25,000. However, with numbers well above their estimates, and since most of the 200 trucks they had hoped to use were in disrepair, the alternative was to walk. Yes, temperatures exceeded 100 degrees F, but the Japanese soldiers walked with the POWs (with an additional 40 pounds of gear). U.S. forces that didn’t sabotage their own trucks to prevent Japanese forces from using them were transported to the facility in those trucks.

Takaaki Yoshimoto, a former Japanese soldier in the Philippines, recounted that “they say that Japanese forces abused the POWs, but that wasn’t our perception. For Japanese soldiers, walking 10-20 km a day, no matter the weather, was par for the course. We just did what we did every day, and the POWs started falling to the ground.” Of course it should be noted that the Allied soldiers were exhausted from the battle, and had been suffering for months from malaria, dysentery, and other diseases.

For the Japanese soldiers, it was also common practice to strike others (usually their fellow soldiers) as a warning when they got out of line, and this wasn’t an exception when dealing with the POWs. Takaaki added that “there were significant differences between the Americans and the Japanese in how they enforced military discipline.”

The U.S. used this incident extensively for wartime propaganda to show Japanese brutality, and those seeds sown in the past continue to be reaped today. But context, as it always does, adds detail to impression, separating fact from fiction.

It seems that Mr. Cohen should have looked a bit beyond the somewhat sophomoric, yet commonly held, historical narrative that the “Americans were the good guys, and the Japanese were the bad guys”. Records from the war have clearly shown that Allied treatment of Japanese POWs wasn’t exactly that of a five star hotel.

One of the more famous recollections of Allied abuses of Japanese POWs came from the diaries (again, primary source) of Charles Lindbergh. In it, he recounted seeing 2000 Japanese POWs being executed at an airfield with machine gun fire, how Allied forces had a penchant for not taking prisoners, and the way in which soldiers would make ornaments and gifts out of the bones of the Japanese war dead.

In another account, one Edgar Jones, who was an embedded Pacific War correspondent, wrote how “we shot prisoners in cold blood, wiped out hospitals, strafed lifeboats, killed or mistreated enemy civilians, finished off the enemy wounded, tossed the dying into a hole with the dead, and in the Pacific boiled flesh off enemy skulls to make table ornaments for sweethearts, or carved their bones into letter openers.”

Were there individual cases of prisoner abuse and war crimes on both sides? Sure. Did either side have nothing better to do than to commit precious manpower, effort, and other resources by making such abuse official policy enshrined in their respective rules of conduct? This is where impression and fact diverge to form our respective historical narratives, and continues to affect everything from diplomatic relations in East Asia to honoring those who fought for their countries.

In the Washington Post article, Mr. Cohen went so far as to accuse Japanese Prime Minister Abe of visiting a Japanese shrine inside Japanese territory. He pointed out that a Japanese Prime Minister visiting Yasukuni, a place where many Japanese war dead, including so-called war criminals, have been enshrined, is “horrendously offensive”.

Perhaps he feels the same way about Arlington National Cemetery and the Air Force Academy Cemertary where Robert McNamara and Curtis LeMay, who were involved in the fire-bombing of hundreds of thousands of Japanese civilians, are laid to rest. That there were U.S. war crimes committed in Vietnam and Iraq goes without saying. But would Mr. Cohen accept a Japanese, Vietnamese, or Iraqi citizen telling the U.S. President not to pay his respects at Arlington? I think not, and nor should he. The soldiers who rest at Arlington gave their lives for their nation, and it’s nobody’s business, but their fellow Americans, how the nation wishes to pay its respects.

As Robert McNamara later put it;

“We burned to death 100,000 Japanese civilians in Tokyo — men, women and children…LeMay said, ‘If we’d lost the war, we’d all have been prosecuted as war criminals.’ And I think he’s right. He, and I’d say I, were behaving as war criminals. LeMay recognized that what he was doing would be thought immoral if his side had lost. But what makes it immoral if you lose and not immoral if you win?”

Much to atone for indeed, but by whom?

Curtis LeMay and Robert McNamara understood that what separated them from the Japanese leaders that were executed for their crimes was one word; “victory”. But as McNamara alluded to so succinctly, the fundamental ideals that form the basis of our moral compass, of our sense of right and wrong, cannot be measured by victory or defeat, even if the historical narrative could.

Mr. Cohen rhetorically questions, “Will Japan’s habit of rewriting its history affect its future?” The answer, unfortunately, is another rhetorical question. “When will the U.S. realize that it has written the wrong history about the war, and concede that Japan is simply trying to salvage the truth?”

This isn’t simply an issue of national pride or personal sentiment. As the U.S. pivots toward the Asia-Pacific region, China is increasingly challenging the world order that the Allies built after WW2. One must realize that China’s grievances against Japan are not rooted in history, but by modern geopolitics, and that the Chinese focus on history is geared toward causing a split in the U.S. – Japan alliance that has kept the peace in Asia for the past 70 years. Mr. Cohen has walked straight into that deceptive trap.

It seems that the U.S. and Japan are faced with one of three choices. The two can split and accept China’s primacy in the Asia-Pacific region, Japan can continue to accept the lies that the Allies disseminated about its nation during and after the war for the sake of preserving the alliance, or the U.S. can face up to the truth and simply move on.

Note that what’s being advocated here isn’t an endless back-and-forth of recriminations and counter-accusations. When Japan advocates the need for “ending the post-war regime”, it isn’t attempting to overturn the relative peace and prosperity that the U.S. and its allies, including Japan, have strived to build and protect for the last 70 years. What it is advocating is to end the false narrative that has continued from the war, so that Japan can actively contribute to the peace and stability in a region where the security environment is rapidly deteriorating.

War is an ugly business. No doubt the war saw countless incidents where the rules of conduct were breached, where men succumbed to their basest instincts, where hatred sown in war overcame the ideals of civility that we all strive for in our moments of peace.

But heading into the 70th anniversary of the end of the war, the time has come to have an honest, if uncomfortable, debate on what really happened, to make sure that the world, victor and vanquished alike, can continue to preserve in peace what we have won through war.